The research plan: Tim Theo Deceuninck

This interview is part of a series of interviews made at the start of Veldwerk III. They offer a glimpse into the practice of the participating artists and sound out how they begin their research project. On this website you can also follow the rest of their trajectory. Speaking here: Tim Theo Deceuninck.

My research for Fieldwork builds on my interest in the photographic device in relation to the landscape. When I started photography I was very much into the analogue: glass plate, silver nitrate, collodion,.... A very chemical lot. At one point I was working on a project on landscape photography and was confronted with the fact that I was working with techniques toxic to that same landscape. From that point on, my entire practice has been a search for alternatives to reverse that chemical process into a sustainable practice.

In that research, I soon came upon Mary Somerville, a 19th century scientist from Scotland. She developed a phototechnical method based on plant material. At that time there were all kinds of experiments going on with photographic material, and Somerville's was successful but fragile. The photographs were not colorfast, and reproduction was not evident. The industrial revolution was in full swing and efficiency, producing on a large scale became important conditions. Moreover, she worked primarily as a scientist and never really did any artistic or photographic productions with it. Because of this, and the fact that women scientists at that time barely received attention, it took a while for her work to be recognized. Her technique is very directing my process and way of working, but equally directing my way of life. In spring I harvest -especially poppies, because they give a deep contrast- , in summer I print, and in winter I can do very little. This in turn gives me time to read, research, and organize the production of the past year.

Letter to Mary S., a publication by Tim Theo, dedicated to Mary Somerville

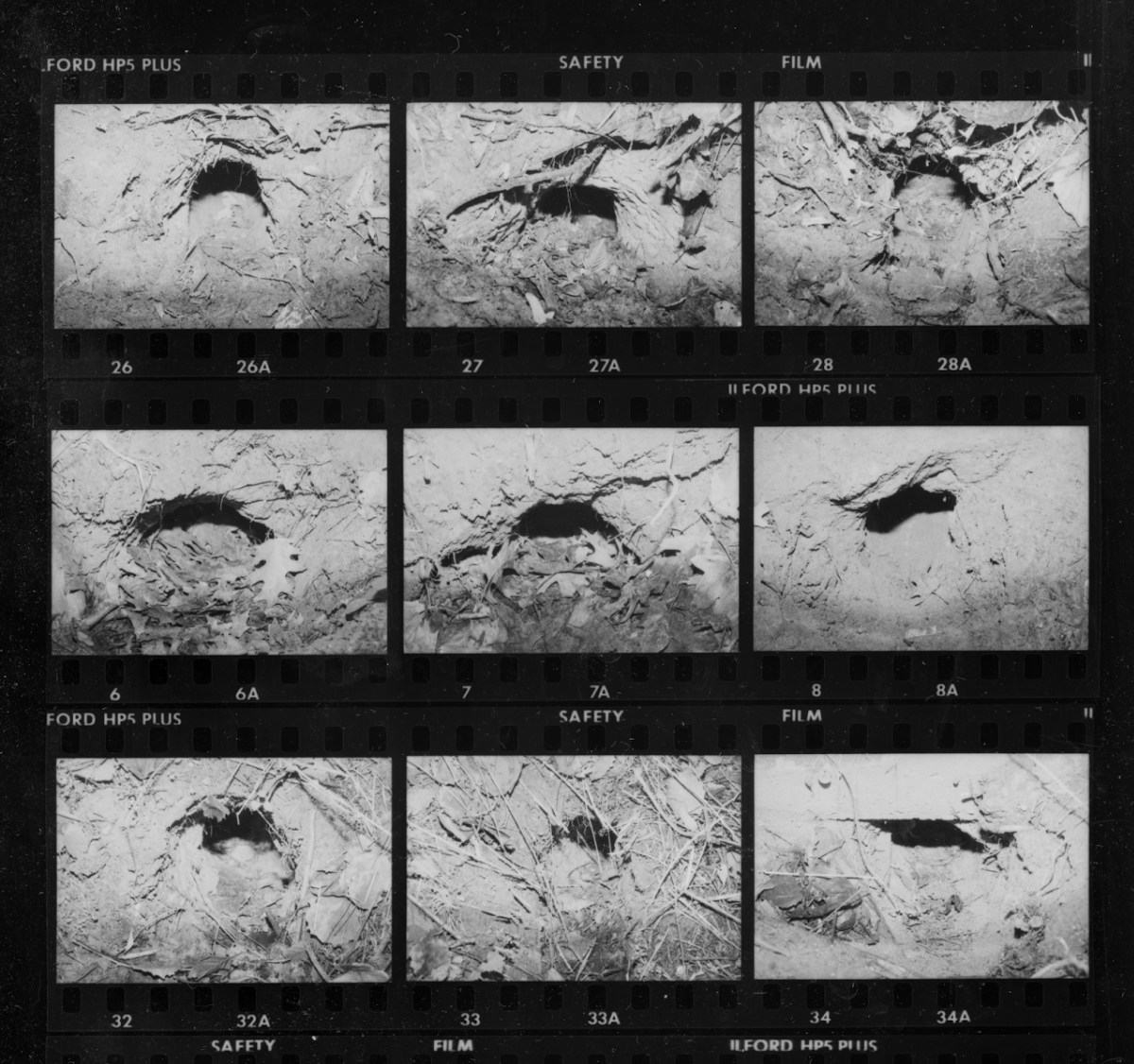

With my research for Fieldwork III, I want to go one step further. I want to use the landscape not only as a material and a theme, but also let it decide the frame. The relationship between photographer and the depicted is dubious, there is always something in between, it is always a representation, a mediation. Without each other you are nothing. That is why I want to look for the absolute basis of photography - a black hole, the camera obscura - in the landscape: caves, rabbit holes, erosion,... In themselves, these are rather banal places without much meaning, but they do shed a direct light on the landscape they give out. Let me put it this way: I mediate a hole, trying to define as little as possible. Every hole I encounter is a possible camera.

It is a way to solidify my relationship with the land and the ground. In this way, I want to break away from an aestheticized landscape. I step away from the typical photographic form, away from industry, resources, the romantic who wants to bring the spectacular landscape to the city. But also from the fact that a photo has to be square. Each of those things are decisions, there is always some form of control. The right time, the right white balance,... I'm looking for a roughness. The negatives are literally in the hole, allowing everything to transform. A beetle runs across the paper, it can get wet; there are an enormous number of factors that can influence it, beyond my control. Even actors that have no voice. That gives space to the question of how I give a voice to the ground, through the landscape, and through a medium. This is not obvious and I am not necessarily trying to offer an answer to it. But by working this way, I do force myself to be constantly working on it.

A camera made by Tim Theo in the hollow of a tree © Leontien Allemeersch

The way I work often starts from theory. Thereby I am less attracted to the theory that describes photography as a stillness or paralysis. The "memento mori," as it is called. I want to do just the opposite. I want to show the living, the circular. For this I find inspiration in Susan Sontag, Donna R. Haraway, Tom Lemaire, Robin Wall Kimmerer,... Flusser's Towards a philosophy of photography is also of great interest to me. In it he describes photography as a black box where an enormous number of factors influence it. For instance, he puts his finger on the entanglement between the pharmaceutical industry and the photographic industry.

I myself like to write after I have worked. It makes me think about what it means to be in a landscape in a much gentler way. It may sound a bit floaty, but on work days I am literally touching plants all day. I feel the sap flows in a tree. Normally I am somewhat skeptical about that, but in that moment, while picking, there is something in that touch that transcends all theory. And then you also write differently, more directly. You don't get stuck in concepts as much.

Photography is often a being on the road, a searching for places. That means a lot of solitary walks and slow actions. That invites you to slow down as a person, too. Sometimes I spend three hours measuring a hole and setting up my camera. Passersby who ask me what I am doing there I give some explanation. Usually I get the question back what the point of all that is. I can't really answer that. Maybe it's because they come to ask me that question? Or because it is good to do something totally useless once in a while?

What exactly the rural means in my practice is a difficult question. For a while I lived along the street in a van. I assumed I would travel around and go into the mountains, but actually I barely went into 'nature'. I found mostly intermediate zones and immersed myself in those micro-environments. A roadside, a piece of forest between fields where animals and plants retreat,... Roads used to connect villages, now roads go around villages. They go straight through the landscape. It is a patchwork where city, nature and the rural are constantly connected. Flemish landscape tourism is a telling example of this. For example, the Kruibeek polder, just outside Antwerp, has a dam where they simulate the tides of the Scheldt, as such creating a polder area. I think it's important to be aware of that tension.

The knowledge surrounding organic dyes and working with plants is strongly related to the idea of community. It is a knowledge that is transmitted from generation to generation, in contact with our ancestors. The community present in my work is both the community of historical rural life and the community of all actors, human and non-human, in the landscape.

Soon I will invite all the artists of Fieldwork III to join me in the fields. That will be a good exercise to test what it can mean to harvest together for a photographic process, what new connections this can bring about or how this collective harvesting can contribute to new harvest rituals. These collective harvesting and working moments are something I would like to work on further. In the past I already did many workshops around sustainable practice (ink making, paper creation with organic material, organic developers,...). I would like to expand this further to create a platform for alternative (photo)graphic applications, where sharing knowledge and making new relationships between human and non-human actors is central.

Collective harvesting during an artist meeting hosted by Tim Theo © Leontien Allemeersch

As a photographer, it is natural to work toward an end result, often in the form of an exhibition. But in my practice, that feels a bit tart. Exhibiting is reframing, a form of aestheticizing. I doubt how that relates to my research questions. Perhaps my work finds its place better in a book? The advantage is that then you can also share your method and your process. When I talk about photography I talk more about the how, the technical, and not about the images I make. Most of the pictures I take were made on the road and rely very strong on that moment of collection. In a book, there is more room to frame that process. Of course, the images have power on their own as well, but I don't want and don't need to be an exhibition photographer. In my previous exhibitions, I always looked for ways to broaden the format of an exhibition. For example, I placed plants in the space. The fact that I also have to give those plants attention at the opening creates a certain tension.

That's also the fascinating thing within Veldwerk: it's not the final product that matters. Sometimes my negatives go black because there is a light leak, or for some inexplicable reason. In the beginning I saw those as failures, but not anymore. It's part of it, and there is never a lost day. The relationship with that place is still established. I look forward to transferring that gentle thinking to others as well.

Exposition by Tim Theo at cc De Schakel, Waregem

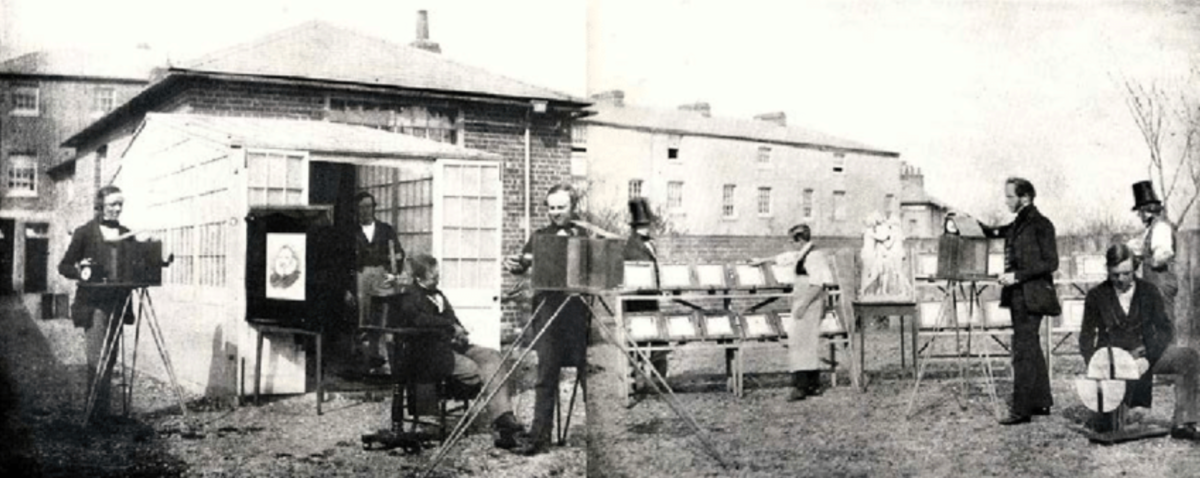

I have a special connection with this image by Henri-Fox Talbot, one of the founders of photography. This is his studio, making contact prints in full sunlight. For me, it shows the essential relationship between natural light and man's urge to capture it. With the photographic pioneers, this relationship is captured in a delicate craft that requires a certain amount of care for the subject matter. It often reminds me of my own workplace when making exposures in full sunlight.

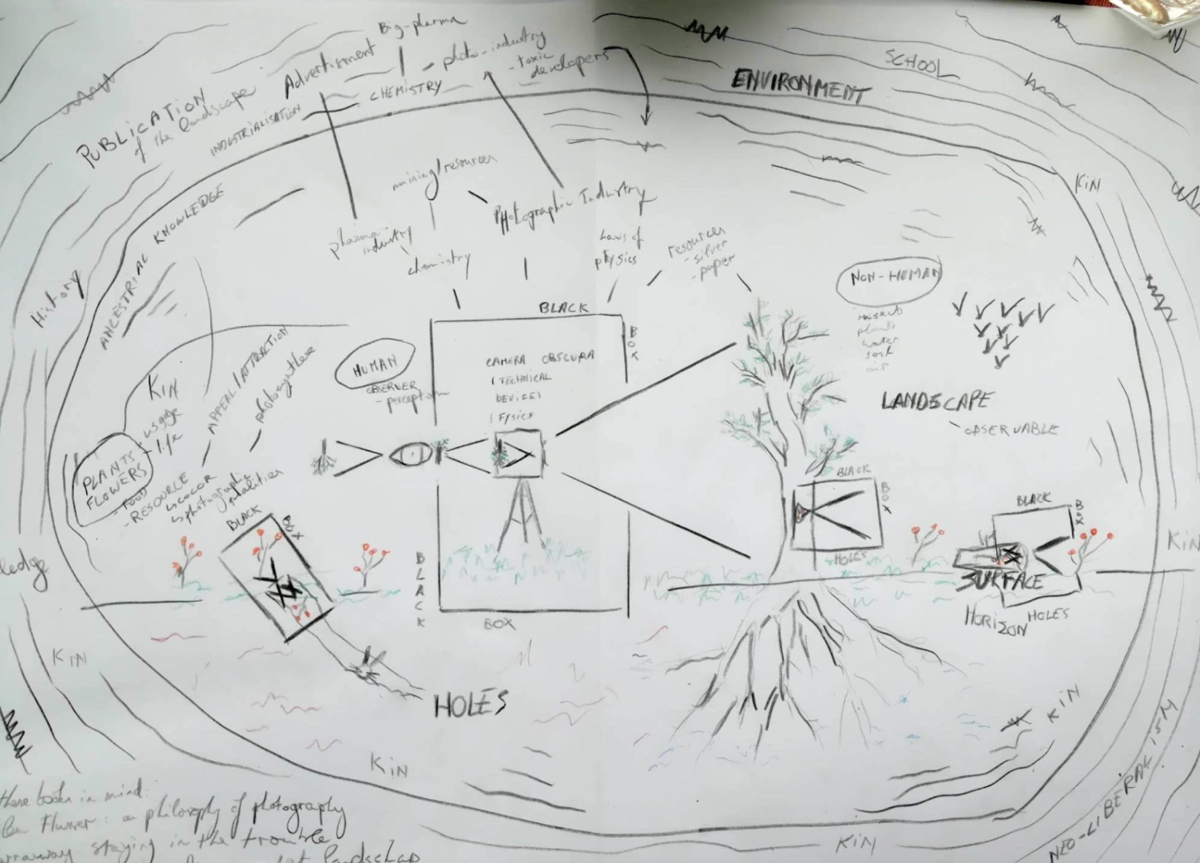

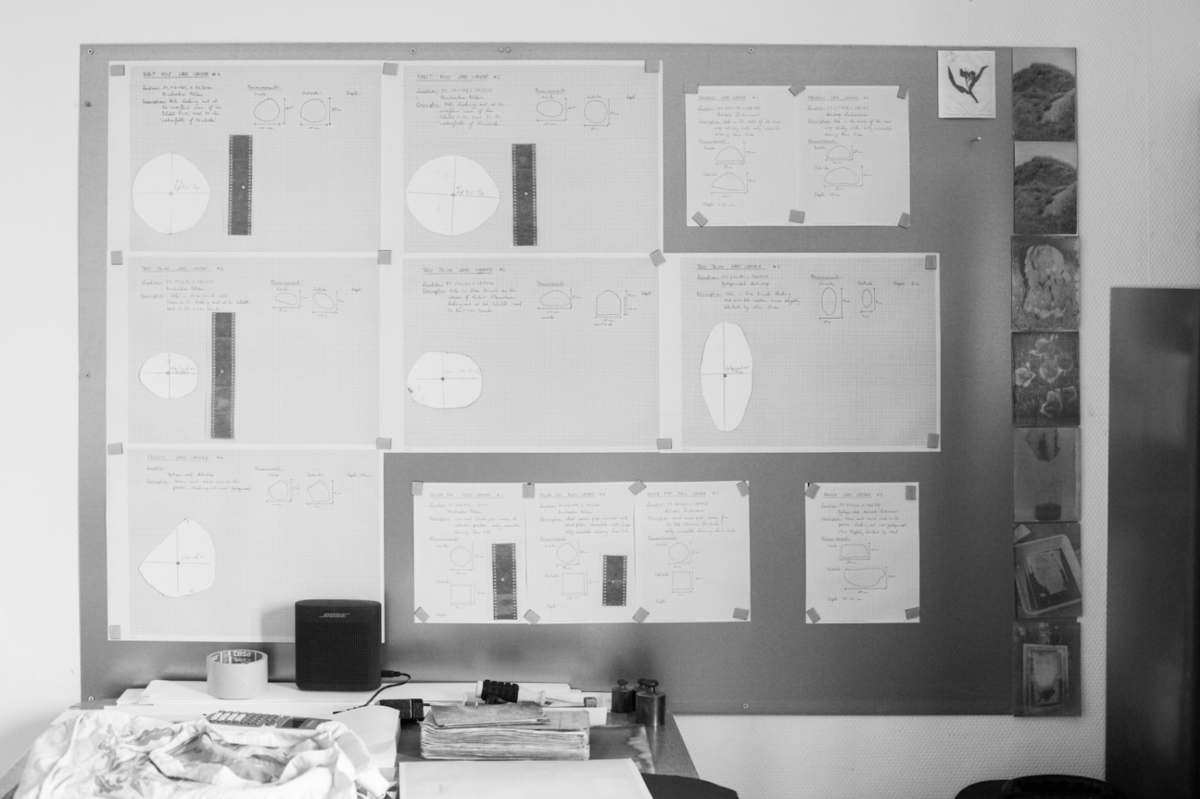

During Areaal (a learning network initiated by Kunstenplatform PLAN B) at Studio Devet, we made a mapping of our practice and how we work. It was interesting to give a place to all the side branches of my process. Also, my studio is currently a collection of measured holes.