Interview: PLAN B on artistic research in non-urban space (Etcetera)

‘The countryside is an extremely interesting environment to work with’

The driving forces behind Veldwerk on artistic research in non-urban areas

Etcetera #164, 01.06.2021, Simon Baetens

What does it mean for an artist to leave the urban context and create work in and about villages, forests and motorways that you don't often think about? How do you facilitate a long-term process? And how do city dwellers view ‘the countryside’ and vice versa? In the artistic research platform Veldwerk by Kunstenplatform PLAN B, eight artists and collectives were given a year to deepen their practice in a local context. Simon Baetens spoke with organisers Leontien Allemeersch, Vincent Focquet and Ewoud Vermote.

FROM LOCAL FESTIVAL TO ARTS PLATFORM

Plan B started out as a festival in the West Flemish village of Bekegem. After four years, you transformed it into a platform for artistic projects developed outside the urban context. What prompted this change?

Leontien Allemeersch: 'Plan B started on a very small scale. Jonathan Bonny, Jane Coppin and I were the original initiators. All three of us come from Bekegem, studied art at the same time, but didn't know each other. That's striking, because Bekegem is a village with only a thousand inhabitants. Conversely, we also noticed that the inhabitants of Bekegem had no idea what we were doing in our art studies in the city. This paradoxical situation formed the starting point for entering into a dialogue with our native village by organising a festival there.’

From the outset, Plan B was locally anchored: we organised residencies in the village, found host families for the artists and converted parish halls and barns into venues for visual art and performance. The team and the festival grew rapidly. Gradually, we talked more and more about what it means to focus on location-specific art: which artists are better suited to the context of a West Flemish village than to a white cube or black box? After four years of sticking to the festival format, we felt like changing tack.

Ewoud Vermote: ‘To really relate to a context, you have to be able to fail, lose your way and retreat to map out the process. For us, this increasingly became the core of Plan B: giving residencies time and focus. With Veldwerk, we invite a manageable number of artists to conduct research for a year without the pressure to achieve a final result. What's more, we also want to share these journeys with an audience. We believe it is valuable to offer people insight into an artistic process.’

Leontien: ‘We realised that there are actually very few organisations that facilitate residencies outside the urban context, even though there are many creators whose practice relates to this. There is a gap there that we want to make visible with Veldwerk. Not every project necessarily took place outside the city: Pim Cornelussen, for example, worked in Bruges, but in his work he questions the idea of the 'urban landscape'.

Where beneath the clouds people are dwarfs, Sidney Aelbrecht – PLAN B Arts Festival 2017 © Tim Theo Deceuninck

MAKING THE INVISIBLE VISIBLE

An annual festival helps you build a certain visibility. With Veldwerk's projects, this is much less obvious: the type of work developed there does not lend itself to traditional forms of presentation and communication. How do you deal with this limited visibility?

Leontien: ‘Making the invisible visible is often an approach not only for the artists, but also in our reflection and communication work. How do you do justice to an artist's development without immediately thinking in terms of results? It is a fact that these kinds of artistic practices are often underexposed and therefore do not reach the general public.’

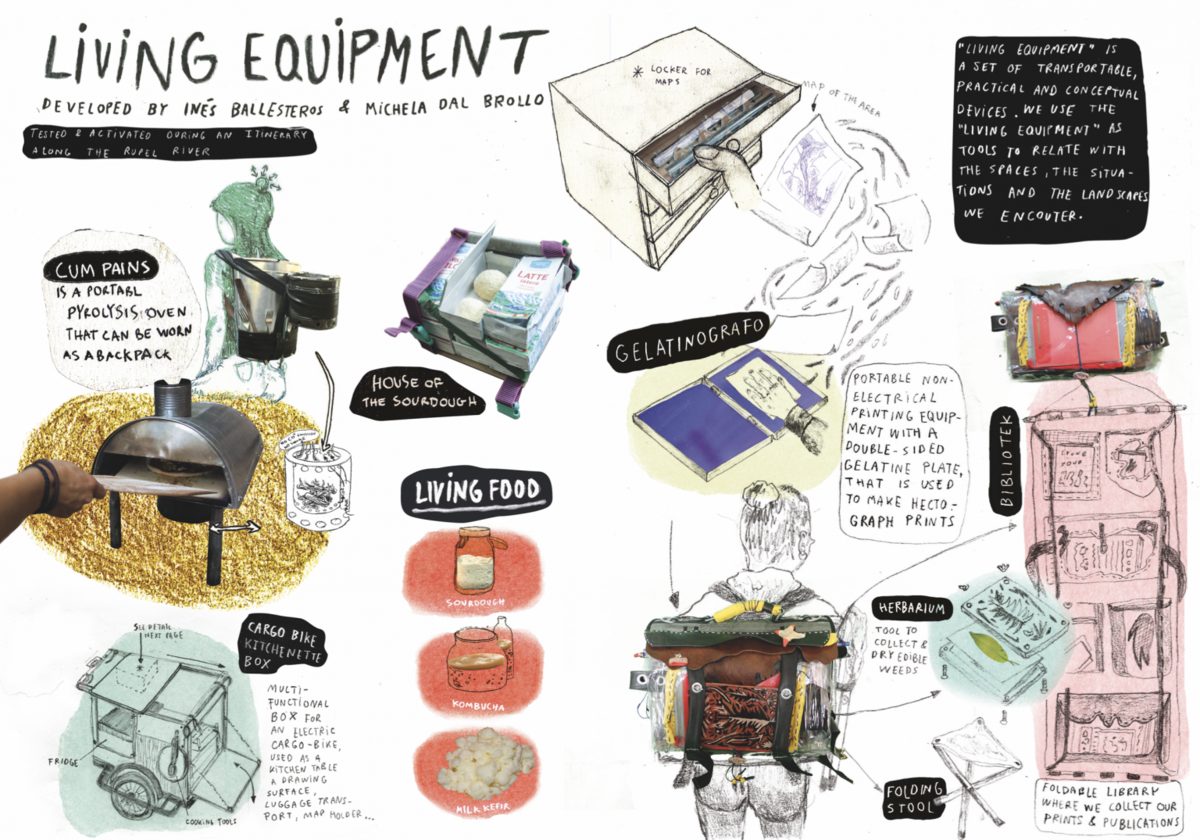

Ewoud: 'However, there are often local collective exchanges between the creators and the residents. Inés Ballesteros and Michela Dal Brollo, for example, collected local ingredients in the village of Noeveren in the Kempen region for their Stone Soup project, which resulted in shared meals. Pim Cornelussen organised an audio walk through Bruges that makes you think about the influence of humans on their natural environment. So there is plenty going on locally. For those who want to follow it all, there is our website and now also the publication Veldwerk 2020-2021.

THE 'COUNTRYSIDE' VERSUS THE CITY

Don't you risk, with every form of publication, creating the effect of artists being sent out to show city dwellers what 'the countryside' looks like?

Leontien: 'That is certainly a potential pitfall. How can we guard against that 'explorer fetishism'?

Ewoud: ‘It is crucial not to view the countryside as an area to be developed. As city dwellers, we don’t need to ‘teach’ anything to that context. We simply see the countryside as an enormously interesting environment to work with.’

'The countryside is simultaneously seen as the vanguard of contemporary upheavals and as a nostalgia for times gone by,'* you write in the publication. To what extent are such views a construct of city dwellers talking about 'nature' while walking in a landscaped park?

Leontien: ‘I was part of a European project on cultural entrepreneurship and realised how strange it is to talk about “the rural context” as a Belgian while Germans, Poles or Swedes are listening. For them, that concept has a completely different meaning.’

Vincent Focquet: 'In a country like Belgium, the countryside is certainly partly a construct. Yet we immediately sense that it is much more challenging to develop an artistic project outside the boundaries of a city. The infrastructure is not always there, it is not clear who you can turn to for financial support. Moreover, the inhabitants of rural areas are not always receptive to our artistic ambitions.'

'Maite Vanhellemont returned to the host family she stayed with during Plan B in 2018 for her research. Marijke and Noël, the couple she follows in Zoals mij gewoon is (As I Am), have repeatedly made statements such as: 'Art, I don't understand it, it's not part of my world'. So there is certainly a disconnect and mutual assumptions in that regard, whether they are justified or not. We have noticed that many people think that contemporary art happens somewhere far away in the city. Clichés such as nude dance performances often come up in such conversations.

'This idea of distance also plays a major role in politics. "Brussels governs us but knows nothing about us": it sounds like a cliché, but there is some truth in it. The city is still too often seen as a model for society tout court. That said, Veldwerk does not aspire to be a sociological study.'

Communicating Vessels, Ciel Grommen & Maximiliaan Royakkers

ON TOUR FROM BARN TO BARN

An important focus in your practice is the relationship between a work and the place where it is developed. How do artists end up in a specific place? Are the location and the concept always inextricably linked? How does the dialogue between idea and place unfold?

Leontien: ‘That dialogue is twofold. Some proposals were linked to a specific place, for others we searched together for a place where research could come into its own. Bert Villa, for example, had initially proposed a methodology for mapping an environment without already having a place in mind. Max Pairon, on the other hand, needed a tree, and in Beerlegem a large tree had fallen, so Beerlegem became the location for his project.’

Vincent: ‘Often, the search for the right location is part of the research. We did not select proposals that we felt could be applied anywhere and therefore did not question the context.

Leontien: 'It's easy to be seduced by black-box logic. "We'll make something in a barn and then tour other barns where we'll repeat the same concept." That kind of thing goes against the core values of Veldwerk, which is working with "what's already there". If the local context doesn't add value to the work, the same applies in reverse.'

EXPERIENCING FOUR SEASONS TOGETHER

A second pillar is time. How do you safeguard and support the long-term processes of the artists you work with?

Ewoud: ‘We give the artists a lot of freedom. If someone wants to work very intensively for two weeks during that period of a year, that should be possible, but a slow process also has its place within Veldwerk. For us, it is an exercise in flexibility: in principle, we answer every question from an artist with ‘Yes, we will!’. Unfortunately, we can't fully compensate the time invested by staff and artists. We definitely want to try to avoid that in the future.'

Vincent: ‘We are not inclined to make the next Veldwerk period much shorter than a year. If you ask an artist to build a relationship with a place or region, you simply cannot expect them to do that in two weeks between other projects. And that's not even mentioning all the other work that an artist has to do: administration, production, reflection, etc. A year is quickly filled. Supporting those components of an artistic practice in a financially sustainable way is still a major challenge.'

Leontien: ‘Going through four seasons together is an intense and educational experience. Staying in touch with someone also means something different for everyone: with some creators we spent a day out and about, with others we spent hours on the phone, and with yet others we exchanged letters.’

Vincent: ‘Shifting the focus from results to research also frees up time to try, fail, start again, and take a step back. When you’re not working towards a presentation, you organise your time differently because you’re not racing against the clock to get your work ready for outside scrutiny.’

Stone Soup, Ines Ballesteros & Michela Dal Brollo

INVENTORYING AS AN ARTISTIC PRACTICE

Much of the work described in the publication uses walking as a form of presentation. Often, this involves mapping or even inventorying the environment in which we usually move around for relaxation, or to clear our heads. Where does this hunger for listing come from?

Ewoud: ‘“Fieldwork” primarily means examining the environment closely and actively scanning what is present.’

Vincent: 'I recognise that tendency to try to understand a new place by mapping it out. That is, of course, also reflected in the title Fieldwork.'

Ewoud: 'When you move house, you do the same thing. You clean every nook and cranny, you map out which parks and shops are in the neighbourhood and in this way you get to know your new living situation. At the beginning of an artistic process, I think that's a logical reflex.'

Vincent: 'It also has a lot to do with otherness: you usually only do mapping when you enter a new context or experience something different from what you know. You're not likely to map your own house, where you've lived for ten years. When I go on a city trip, for example, I want to see as much as possible and be able to take the underground without having to look at a map. In Brussels, where I live, I have no idea how the underground works. Finally, I think mapping is also an attempt to deal with being alone by giving yourself a task."

That silly Jan, Maix Pairon © Leontien Allemeersch

‘INSTANTANEOUS ARCHAEOLOGY’

In recent years, there has been a tendency to focus on the practice or methodology behind a work of art, or even to completely blur the boundaries between process and result. How do you communicate an artistic practice in its entirety to an audience?

Vincent: ‘At its core, Veldwerk is a platform that facilitates long-term, location-specific residencies. We are much less interested in the movement to subsequently display the research that emerges from these residencies as a work of art. Most of the artists we work with do not see the process within Veldwerk as a stand-alone work, but rather as a development trajectory or deepening within their broader practice.’

Ewoud: ‘We may look at it differently, because we always ask ourselves how we can communicate what is happening, how we can let people be part of that development. We don't ask the artists to view their process as a work of art.’

Leontien: ‘No, we ask them how they can make their process shareable and think along with them.’

That's a fine line, isn't it? As soon as you ask someone to make something shareable, aren't you asking them to produce something?

Leontien: ‘Absolutely, and the question of the best communication strategy is very relevant; we can still make great strides in that area. The artists often said, “I have nothing to share.”’

Vincent: ‘It feels strange to send artists on a journey and not communicate about it. That seems very selfish. Which is actually absurd, because it raises the question of who is working for whom.’

Ewoud: ‘We try to make the traces left behind by the creators shareable, rather than expecting them to do so themselves. But it’s a valid question why we want to fill a website in addition to these extremely local events.’

You are a kind of archaeologist, but without any time between the event and the discovery.

Vincent: ‘Instantaneous archaeology.’

As an artist, it's nice to have good documentation of your work. Is the internet really the most suitable place to unlock those traces?

Vincent: 'It is the place where our urban art friends find their way, yes. But local exchange is of course much more valuable and cannot simply be summarised in a blog post.'

---

Fieldwork 2020-2021 is a publication by Arts Platform PLAN B. Fieldwork is a project by Arts Platform PLAN B.

Participants in Fieldwork 2020-2021: Pim Cornelussen (NL), Inés Ballesteros & Michela Dal Brollo (ES/IT), Ciel Grommen & Maximiliaan Royakkers (BE), Max Pairon (BE), Sibran Sampers (BE), Maxime Vancoillie (BE), Maite Vanhellemont (NL) and Bert Villa (BE).

* Paraphrasing a quote by architect Rem Koolhaas