Text & poster 'Becoming Terrestrial' - Tim Theo Deceuninck x Timo Bonneure

For Fieldwork III, Tim Theo Deceuninck investigated the industrial landscape around the Scheldt estuary. He used holes in the landscape as the basis for a camera obscura, which he then used to photograph the landscape itself. This research resulted in the publication Becoming Terrestrial, published by SO-RI. He also wrote a text that was designed in the form of a poster, designed by Timo Bonneure.

Language: English

Free to collect in Ghent or Brussels. Postage available at extra cost.

For information and to order, click here.

-

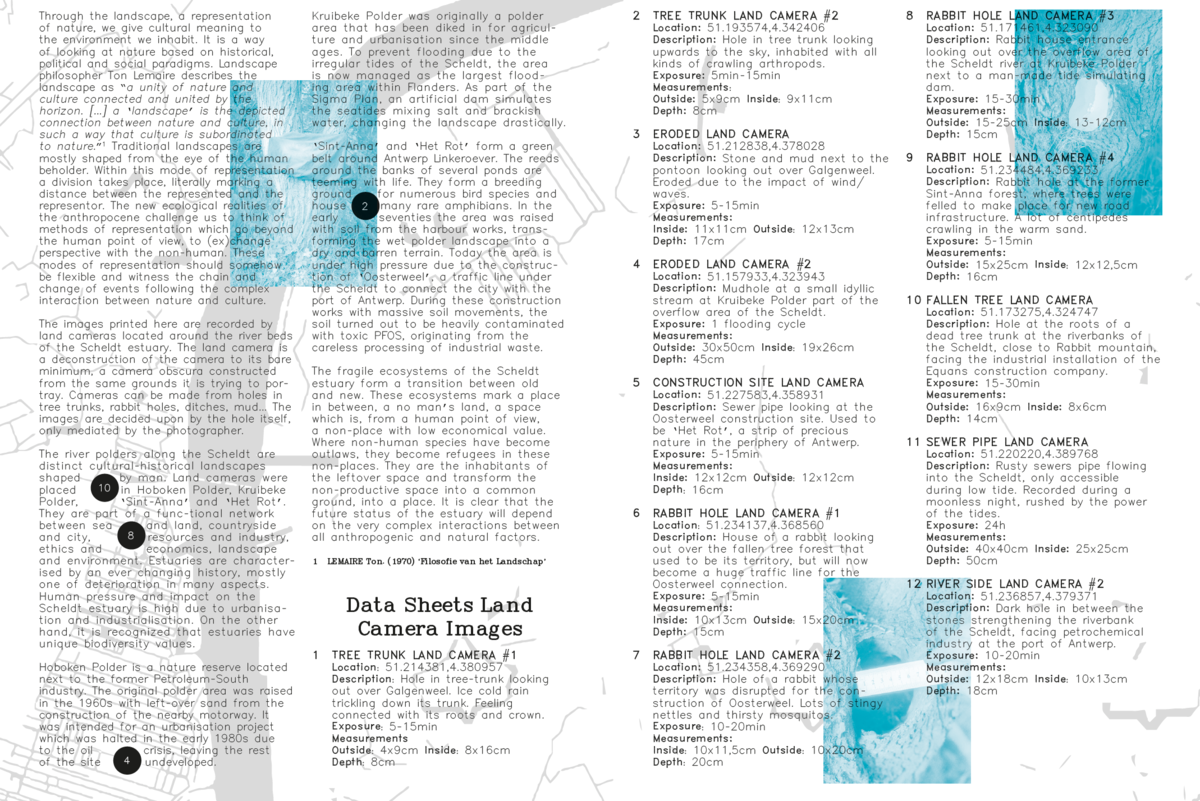

Through the landscape, a representation of nature, we give cultural meaning to the environment we inhabit. It is a way of looking at nature based on historical, political and social paradigms. Landscape philosopher Ton Lemaire describes the landscape as “a unity of nature and culture connected and united by the horizon. [...] a ‘landscape’ is the depicted connection between nature and culture, in such a way that culture is subordinated to nature.”1 Traditional landscapes are mostly shaped from the eye of the human beholder. Within this mode of representation, a division takes place, literally marking a distance between the represented and the representor. The new ecological realities of the Anthropocene challenge us to think of methods of representation that go beyond the human point of view, to (ex)change perspective with the non-human. These modes of representation should somehow be flexible and witness the chain and change of events following the complex interaction between nature and culture.

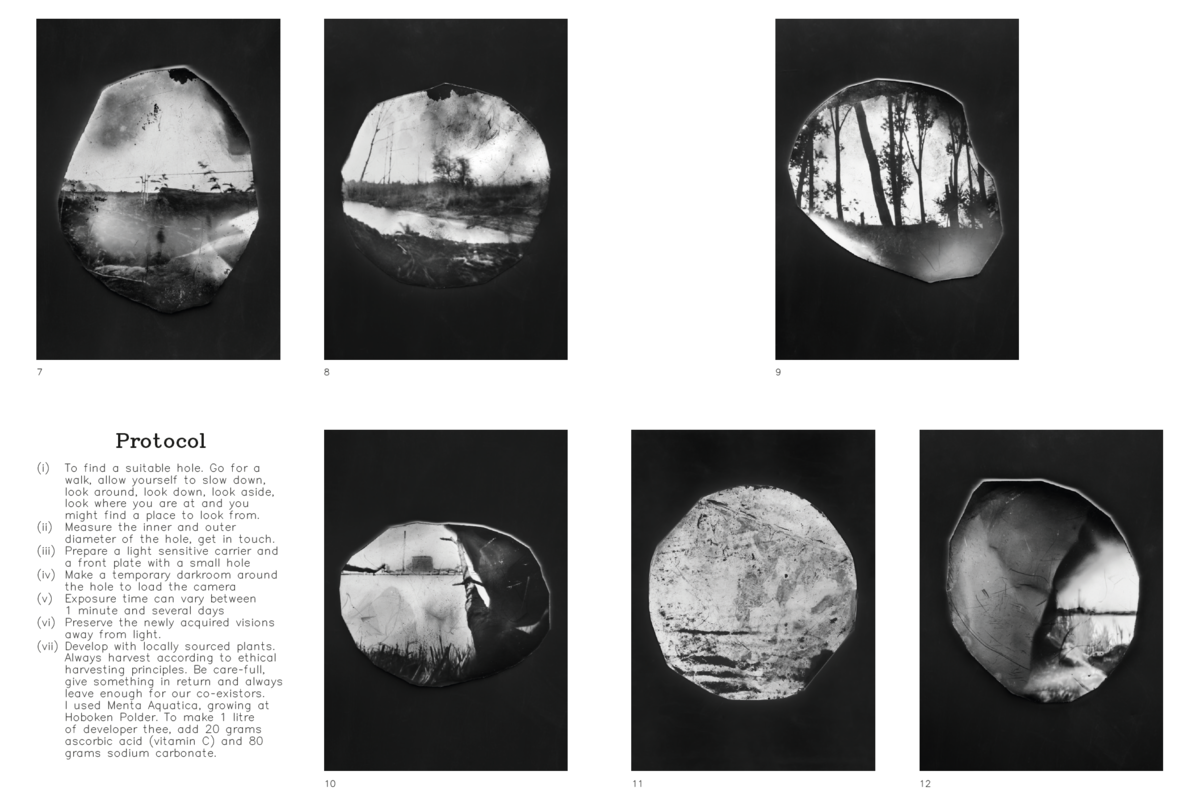

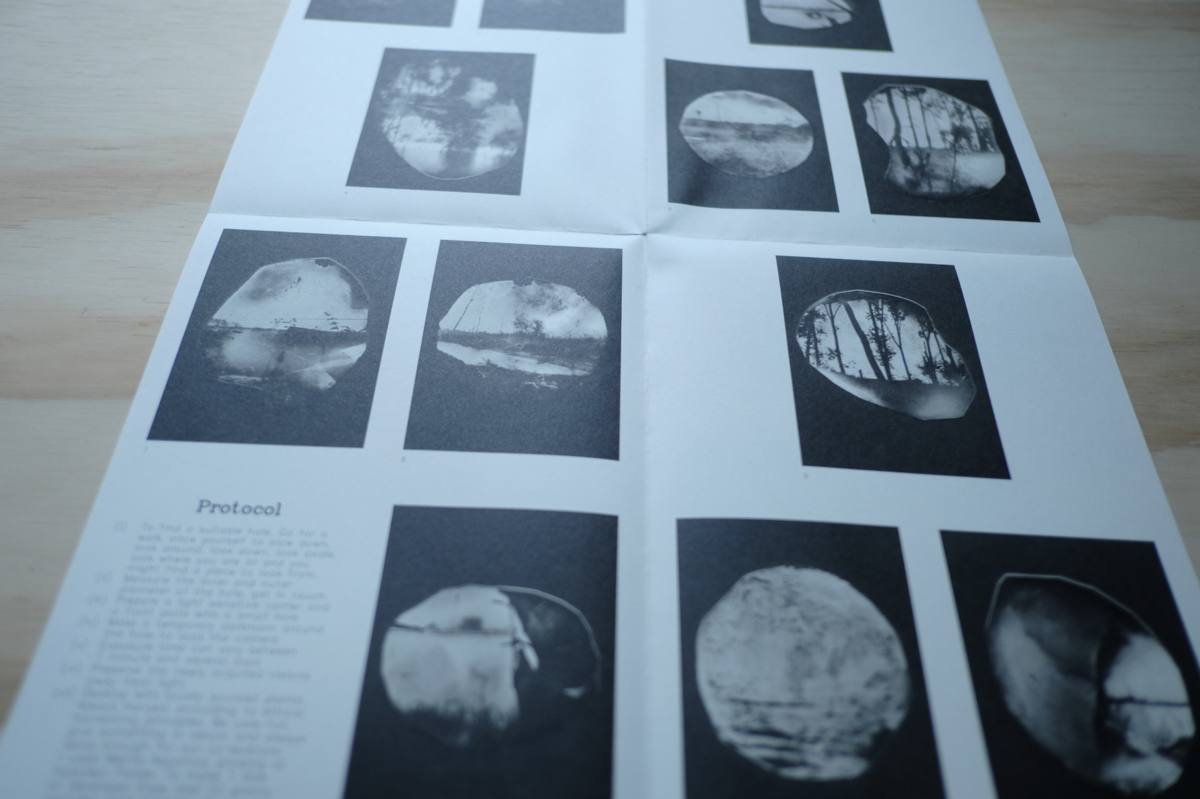

The images printed here are recorded by land cameras located around the river beds of the Scheldt estuary. The land camera is a deconstruction of the camera to its bare minimum, a camera obscura constructed from the same grounds it is trying to portray. Cameras can be made from holes in tree trunks, rabbit holes, ditches, mud... The images are decided upon by the hole itself, only mediated by the photographer.

The river polders along the Scheldt are distinct cultural-historical landscapes shaped by man. Land cameras were placed in Hoboken Polder, Kruibeke Polder, ‘Sint-Anna’ and ‘Het Rot’. They are part of a functional network between sea and land, countryside and city, resources and industry, ethics and economics, landscape and environment. Estuaries are characterised by an ever-changing history, mostly one of deterioration in many aspects. Human pressure and impact on the Scheldt estuary is high due to urbanisation and industrialisation. On the other hand, it is recognised that estuaries have unique biodiversity values.

Hoboken Polder is a nature reserve located next to the former Petroleum-South industry. The original polder area was raised in the 1960s with leftover sand from the construction of the nearby motorway. It was intended for an urbanisation project which was halted in the early 1980s due to the oil crisis, leaving the rest of the site undeveloped.

Kruibeke Polder was originally a polder area that has been diked in for agriculture and urbanisation since the Middle Ages. To prevent flooding due to the irregular tides of the Scheldt, the area is now managed as the largest flooding area within Flanders. As part of the Sigma Plan, an artificial dam simulates the sea tides mixing salt and brackish water, changing the landscape drastically.

Sint-Anna and Het Rot form a green belt around Antwerp Linkeroever. The reeds around the banks of several ponds are teeming with life. They form a breeding ground for numerous bird species and house many rare amphibians. In the early seventies, the area was raised with soil from the harbour works, transforming the wet polder landscape into a dry and barren terrain. Today, the area is under high pressure due to the construction of ‘Oosterweel’, a traffic line under the Scheldt to connect the city with the port of Antwerp. During these construction works with massive soil movements, the soil turned out to be heavily contaminated with toxic PFOS, originating from the careless processing of industrial waste.

The fragile ecosystems of the Scheldt estuary form a transition between old and new. These ecosystems mark a place in between, a no man’s land, a space which is, from a human point of view, a non-place with low economic value. Where non-human species have become outlaws, they become refugees in these non-places. They are the inhabitants of the leftover space and transform the non-productive space into a common ground, into a place. It is clear that the future status of the estuary will depend on the very complex interactions between all anthropogenic and natural factors.