The research plan: Maxime Vancoillie

This interview is part of a series of interviews conducted at the start of PLAN B/Fieldwork, the collective research project on art outside the city by arts platform PLAN B. The interviews offer a glimpse into the practice of the eight participating artists and explore how they are approaching their research projects. You can also follow the rest of their journey on this blog. Maxime Vancoillie (1991, BE) works at the intersection of architecture and visual art. During PLAN B/Fieldwork, she collects dreams along the N9 regional road through interviews. Her research gives shape to the architectural forms that appear in those dreams.

For me, a research process always starts from the idea that our world contains countless micro-worlds. Such a micro-world can take on different scales: your own home, the neighbourhood you relate to, the city you live in, and can be real, fictional or virtual. But a certain state or condition can also determine the boundaries of such a micro-world: 'being on the run', 'wandering', 'being settled'... Everyone crosses one or more worlds over time. In this way, we build our own collection of spaces that surround us every day, that we remember or imagine, where we have (never) been, that we have (never) seen.

During a research project, I immerse myself in a specific world and its inhabitants and users. The field of research thus becomes a hybrid collection of worlds, spaces and space users. In doing so, I try to put as many words as possible to the things I observe, whether visible or invisible. By naming things, we define the world. Finding, organising and indexing the right words is a construction process in itself. The result is a framework of keywords, concepts and phenomena; a kind of temporary residence where all the research material is stored. Over time, I begin to translate insights from that base into reflection models: 3D models that have a different meaning and purpose in each phase of the process. These are a means of developing research questions, but also of bringing insights together towards the end.

Since 2014, I have been writing down my night dreams, a collection of more than 200 dreams to date. When drawing some of them, I was amazed to see that they seemed to follow a certain architectural logic. The relationship between the emotional charge of the dream and the architecture dreamt, and how they influence each other, is also particularly interesting. It is not concrete architecture of reality, where all elements are bound by gravity and remain structurally sound. It is an architecture built from layers of time, from memories and imagination, from physical and emotional experiences. The dream allows me to investigate the influence of the built environment on that inner world. This immediately raises a lot of questions. Are there collective spatial patterns to be found in the dreams of inhabitants of a particular landscape? How does the built environment penetrate dreams? Are dreams culturally determined, or can universal 'inner' archetypes be distinguished?

The fog city is the phenomenon whereby one large, diffuse city takes the place of the former division between city and countryside. Cities are expanding, and the countryside is also taking on a more urban appearance. This nebula city stretches along stone roads, converges in (sleeping) villages and is structured in the form of allotments. Within Flanders, the N9, a regional road connecting Brussels with Ostend, seems to be a cross-section of this phenomenon. The road is a characteristic linear landscape of farmhouses and Spanish-style imitation villas, garden centres and cafés, dance halls, bus stops, hedges and fences, showrooms, church towers, saunas, fountains and statues, brothels, meadows, petrol stations and flats...

My project has an open ending. This gives me the freedom to work associatively and focus on the process. During a 'gathering route' along the N9, I go in search of the residents and their dreams. The dream is reconstructed through writing and sketching, after which I return to the residents with scale models. These then serve as support for in-depth interviews about their experience of the dream. Does your everyday environment feature in your dreams? What does the public space look like? In which spaces are you afraid? I bring these individual experiences together on a map, thus depicting a collective imaginary landscape. From there, I can ask new questions as I build. What kinds of dreams recur frequently? Are they dreams of escape, dreams of fear, dreams of security...? What archetypes can I deduce? Safe places, hiding places, public places, private places, closed places, open places...? In a final phase, this map can serve as a blueprint for structures that I would build on a larger scale along the N9. In this way, the dream takes its place in reality once again and initiates an in-situ dialogue.

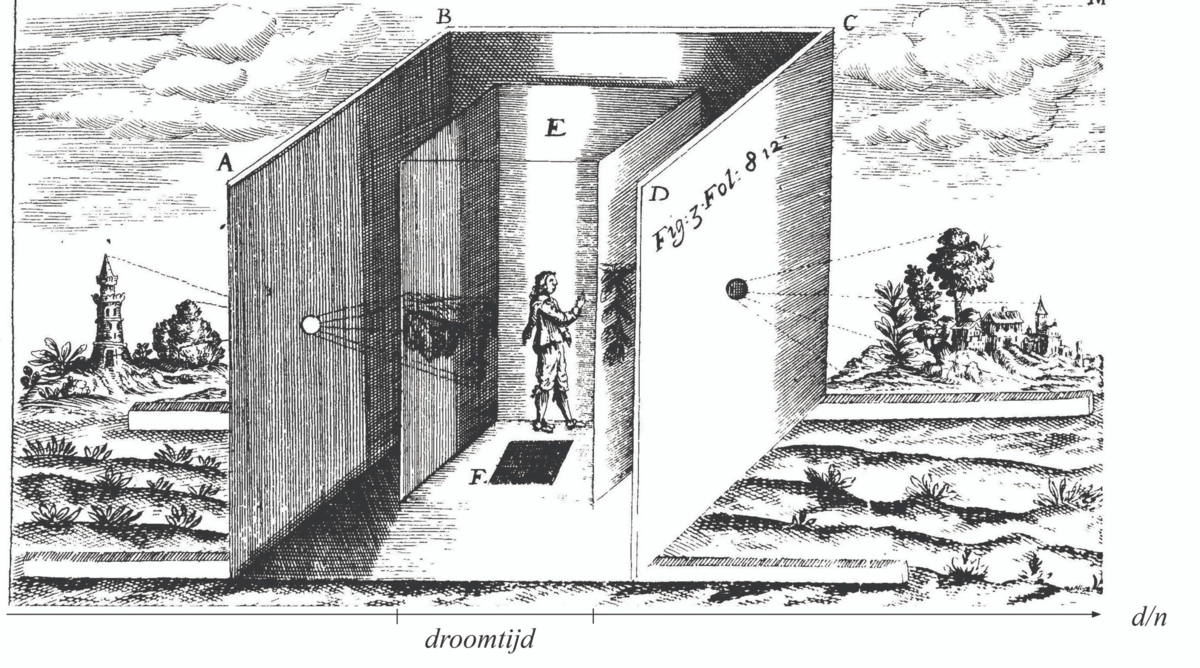

I see this image (see above, ed.) of the camera obscura as a metaphor for my research. A camera obscura (dark room) is a darkened space with a small hole in one of the walls. The light entering through this hole projects an image of the outside world onto the opposite wall. I have added one element to the engraving by inventor Athanasius Kircher: a timeline that situates day and night. The room depicted is the mechanism of the night dream. Fragments of reality enter the room on the left, after which a distortion of reality usually occurs, just as the camera obscura projects the image upside down. As we step back into the day on the right, the dream regains its place in reality.

Read more about Topography of the Night - 01 - The Mist City by Maxime Vancoillie here.