The Research Plan: Joris De Rycke

This interview is part of a series of interviews conducted at the start of Fieldwork II. They offer a glimpse into the practice of the six participating artists/collectives and explore the way in which they approach their research projects. You can also follow the rest of their journey on this website. Here, Joris De Rycke talks about his project 'Ruderalia'.

Mapping and identifying wild plants is something I have been doing for a long time. Initially, this activity was not directly related to my artistic practice, but lately the two have begun to converge. For me, my artistic activities and the scientific systematics of ecology are constantly intertwined. Both are very specific frameworks for viewing the world. They are based on an in-depth study of the visual world without necessarily having any practical use. I know people who spend day and night studying lichens or the sexual characteristics of aphids. When someone delves so deeply into a particular subject, the comparison with an artistic practice is not far-fetched. A research-based project such as Veldwerk ensures that my practice, which is partly botanical and partly artistic, can take on a clear form and lead to something that is finished.

A film seems to me to be an ideal form in which to explore and present this research in all its complexity. Through that medium, you come quite close to the experience of 'seeing for yourself' or 'remembering something', while as a creator you can fill in and steer this experience very precisely. Casting such research into a museum exhibition quickly becomes very abstract and far removed from the direct experience of seeing.

Each screening is a kind of exhibition that you build up and break down again and again to show in a different context. It would be great to be able to present the film both within different plant working groups and at an experimental film festival.

For my film, I am looking for places with a certain ambiguity. I want to limit myself to places with a high diversity of plants and nature, but which are not nature reserves. Places where no real conservation takes place. For example, I want to work around the mine spoil tips in Genk. They have an unclear status: monument, industry, waste, past, future... The coal that was mined there consists of the remains of plant species that became extinct 300 million years ago. On such a mine slag heap, you walk on the remains of the first forests that ever covered the earth. Such places are much more inspiring to me than nature reserves that are managed to look like nature.

These are places that are not consistently maintained, are usually polluted, and often only exist for a very short time. They have no protection as nature, but are within reach of the city and its property developers. My film will therefore also be an archive of places that will change beyond recognition.

For my apple tree project, in which I am creating a collection of different varieties of apple trees from discarded cores, I have often sought out such places. I start from the principle that apple trees that grow from the seeds of a core do not belong to an existing variety such as Jonagold or Granny Smith, but through cross-pollination have very different characteristics from the apple they come from. I find these apple trees next to railway lines, on abandoned industrial sites, or in car parks where many truckers stop (and throw their cores on the verge). I revisit these places when the trees are bearing apples, select the most interesting varieties, and return during the winter to cut twigs from the trees and graft them. This project is ongoing during my research for Veldwerk, but now I also take my camera with me to document the locations themselves.

People who spend a lot of time in a particular place become a kind of caretaker of that place. That is why I also want to focus on interactions with local residents and regular passers-by. My research could just as easily take place within a city; from a purely botanical point of view, it is the same method. What is different, however, are the encounters that take place. At a busy intersection in the city, it is often more difficult to strike up a conversation than on a deserted road where someone passes by every hour. The people who pass by there have usually made a very conscious choice to be there at that moment. That makes me curious about the interactions people have with the places I map. Someone who fishes at the same cove every week has a more profound interaction with that place than I do. That can lead to an interesting conversation, even if it's just to film what kind of fish he has in his bucket.

I will be satisfied with my film if there is a certain complexity to it. What often bothers me about nature documentaries is that you see a few lions and a few zebras, but the mushrooms and grass that grow there are not mentioned. I also want to show the less visible aspects, without reducing them to a story. If there is a story in it, it comes from working on the same theme 24 hours a day. Then I automatically start to see a lot of connections, a special state of being with a clear focus. I hope I can translate that personal experience through editing. It certainly doesn't have to be a coherent story; on the contrary, editing is always a kind of collage. I would like it if people couldn't immediately summarise what the film was about afterwards.

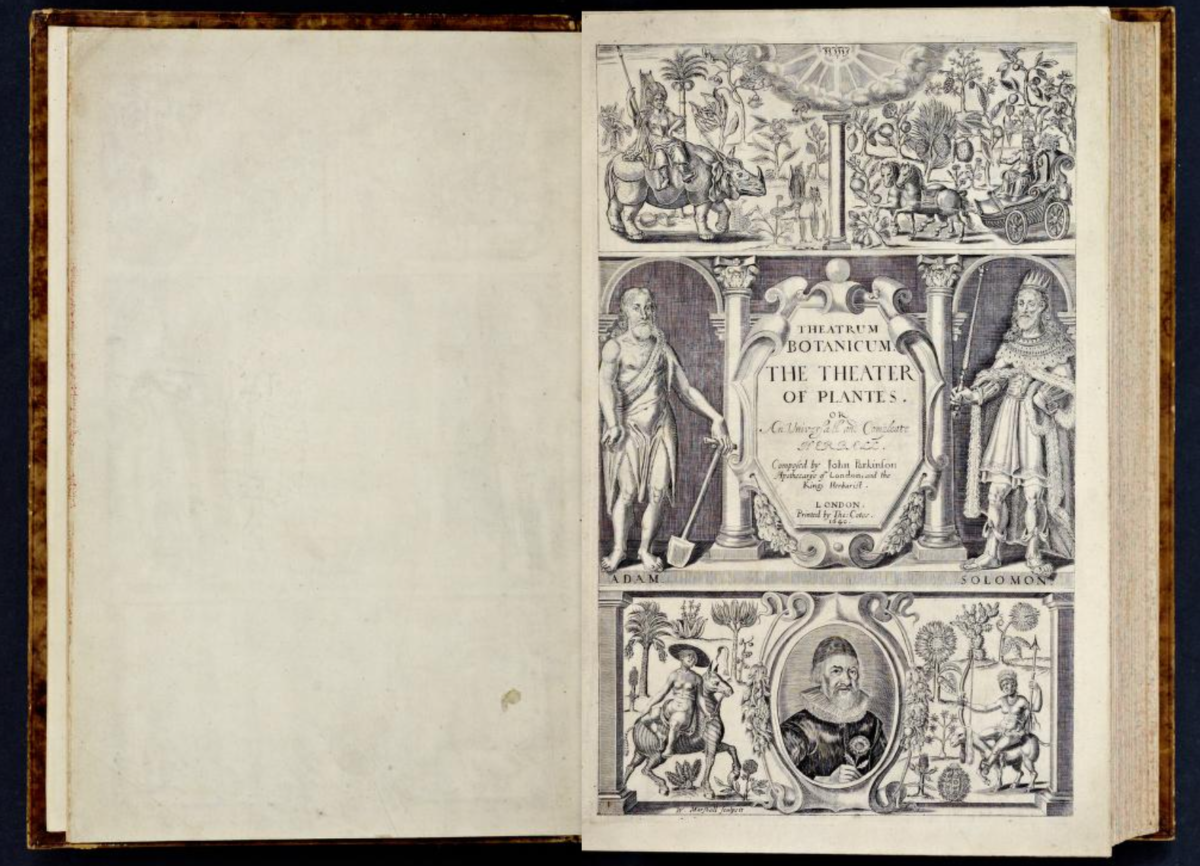

John Parkinson's Theatrum Botanicum (1640) is an important herbal book in the English-speaking world, somewhat comparable to Rembert Dodoens' Cruydtboek (1554). Personally, I do not find Theatrum Botanicum necessarily more interesting than other herbal books, but the title certainly appeals to my imagination. Theatrum was often used in the titles of descriptive works at that time. For example, Abraham Ortelius's first world atlas was titled Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. A literal interpretation as a plant theatre corresponds to one of the ways in which I want to interpret the film. By selecting a number of plant species for each location that are exceptional and at the same time specific to that location, and following them throughout their growing season, they become protagonists in the film.